By Adenike Alao

In Lagos, real estate isn’t just an asset class – it’s a stage where wealth, influence and policy collide. From Ikoyi’s glass towers to the fast-rising corridors of Ibeju-Lekki, the market rewards capital and connections. But while headline sales and gated estates grab headlines, the city’s housing shortfall keeps growing: millions of Lagosians remain priced out or forced into crowded, informal living.

The spectacle: luxury, foreign capital and price momentum

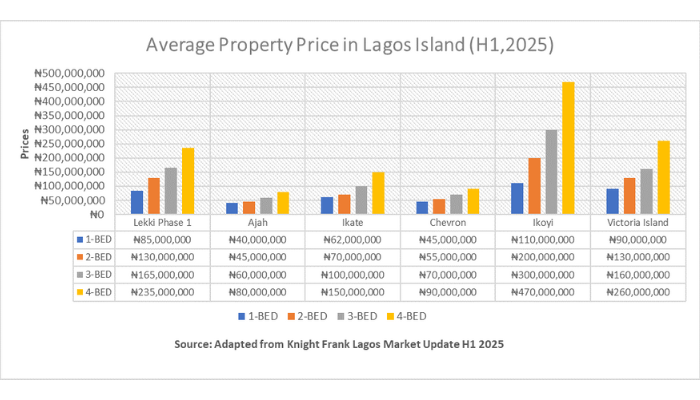

Walk around Ikoyi and Banana Island and the story is obvious: ultra-luxury homes, embassies and corporate towers. Market trackers put average asking prices in Ikoyi in the ₦1–1.5 billion range (and much higher for flagship properties), driven by strong demand from high-net-worth individuals, firms and foreign buyers. Developers and investors see these neighbourhoods as safe stores of value – especially when inflation and currency volatility erode cash holdings.

That concentration of capital creates rapid price appreciation in prime corridors while also pulling construction and design talent toward high-end projects. New towers, mixed-use developments and branded residences signal that Lagos remains attractive to capital – but that attractiveness is unevenly distributed.

The growth frontier: Ibeju-Lekki and the promise (and cost) of big projects

Ibeju-Lekki has become the visible axis of Lagos’s next chapter. Large infrastructure – the Dangote Refinery, Lekki Deep Sea Port and related logistics – has pushed land values and spurred mass residential schemes and estate launches. Plot and developer prices in parts of Ibeju-Lekki still read as “affordable” to investors compared with Ikoyi, which explains the surge of speculative buying and large-scale masterplans.

But the industrial-led boom has trade-offs: displacement of fishing and farming communities, environmental concerns from wetland reclamation, and unmet promises on inclusive job creation and resettlement for affected residents. Reports from the area describe lasting effects on livelihoods for communities these projects surrounded.

The gap: huge unmet need for affordable housing

The big, uncomfortable headline is the housing deficit. Recent surveys put Lagos’s housing shortfall in the millions – estimates show the deficit growing to roughly 3.4 million units in 2025. Supply has improved compared with a decade ago, but demand from rapid urban migration and household formation has outpaced that supply, and most new units target the middle and upper segments rather than low-income needs. That mismatch is why rents and prices remain unaffordable to large swathes of the city’s workforce.

Why the market fails the many

Developer economics: High material costs, constrained finance and long approval cycles push developers toward higher-margin projects where returns justify the risks.

Weak mortgage market: Mortgage penetration in Nigeria remains low relative to developed markets, making owner-occupancy via formal finance difficult for most buyers. (See Central Bank and housing sector analyses for context on finance constraints.)

Land and planning bottlenecks: Fragmented land records, titling disputes and protracted planning approvals raise costs and slow delivery of affordable schemes.

Policy and funding gaps: Public housing interventions exist but lack the scale or predictable funding to close the deficit quickly.

Opportunities that could narrow the divide

Lagos’s private sector and policymakers can take practical, scalable steps to bring supply to where it’s needed:

Scale incremental housing and rental models: Modular, incremental build-to-rent and single-room occupancy (SRO) units, financed by institutional investors, can provide quality rental stock at lower price points.

Unlock affordable finance: Deepening mortgage markets, blended finance vehicles and long-tenor construction loans – paired with credit enhancements – would allow more developers to build at lower margins sustainably.

Land-use reforms and digitised records: Faster, cheaper titling and streamlined approvals reduce development costs and time-to-market.

Localised inclusion clauses: Major projects in Ibeju-Lekki and elsewhere should include enforceable community benefits – skills programs, local employment quotas and practical livelihood restoration – to reduce the social cost of large developments.

What this means for Lagosians

For investors and HNW buyers, Lagos remains an attractive store of value. For ordinary Lagosians, however, the city is becoming more expensive and less forgiving: longer commutes, crowded rentals and pressure on informal settlements. Bridging that gap requires aligning public policy, capital markets and developer incentives toward scalable, lower-cost housing solutions – not just the next luxury tower.

Meta description: Lagos’s property market is a study in contrasts: booming luxury corridors and speculative frontier growth in Ibeju-Lekki coexist with a housing deficit of roughly 3.4 million units. What explains the gap – and how can policy and capital bridge it?

Source: Businessday